|

A BILL GRIFFITH BIO

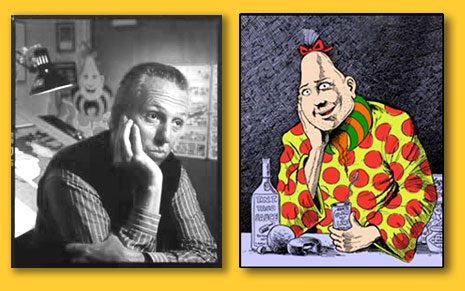

"Are we having fun yet?" This non sequitur utterance by the clown-suited

philosopher/media star Zippy the Pinhead has become so oft-quoted that

it is now in Bartlett's Familiar Quotations. Zippy has in fact become an

international icon, even appearing on the (former) Berlin Wall. Zippy's

creator, Bill Griffith, began his comics career in New York City in 1969.

His first strips were published in the East Village Other and Screw

Magazine and featured an angry amphibian named Mr. The Toad.

He ventured to San Francisco in 1970 to join the burgeoning underground

comics movement and made his home there until 1998. His first major

comic book titles included Tales of Toad and Young Lust, a best-selling

series parodying romance comics of the time.He was co-editor of Arcade,

The Comics Revue for its seven issue run in the mid-70s and worked with

the important underground publishers throughout the seventies and up to

the present: Print Mint, Last Gasp, Rip Off Press, Kitchen Sink and

Fantagraphics Books. The first Zippy strip appeared in Real Pulp #1

(Print Mint) in 1970. The strip went weekly in 1976, first in the Berkeley Barb

and then syndicated nationally through Rip Off Press.

In 1980 weekly syndication was taken over by Zipsynd (later Pinhead Productions),

owned and operated by the artist. Zippy also appeared in the pages of the National

Lampoon and High Times from 1977 to 1984. In 1985 the San Francisco Examiner

asked Griffith to do Zippy six days a week, and in 1986 he was approached by

King Features Syndicate to take the daily strip to a national audience.Sunday

color strips began running in 1990. Today Zippy appears in over 200 newspapers

worldwide. There have been over a dozen paperback collections of Griffith's work

and numerous comic book and magazine appearances, both here and abroad.

He became an irregular contributor to The New Yorker in 1994. Griffith's inspiration

for Zippy came from several sources, among them the sideshow "pinheads" in

Tod Browning's 1932 film Freaks. The name "Zippy" springs from "Zip the What-Is-It?"

a "freak" exhibited by P.T. Barnum from 1864 to 1926. Zip's real name was

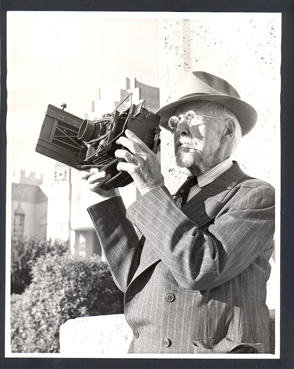

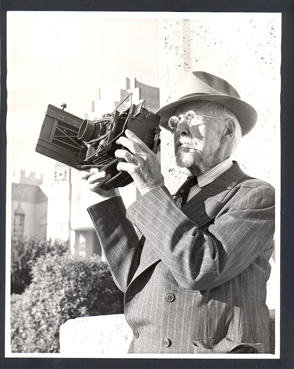

William Henry Jackson (below), born in 1842. Coincidentally, Griffith (as he discovered in

1975, five years after creating Zippy) bears the same name. He was born

William Henry Jackson Griffith (in 1944), named after his great-grandfather,

well-known photographer of the Old West William H. Jackson (1842-1941).

He is the author of four graphic novels: "Invisible Ink" (Fantagraphics Books, 2015), "Nobody's Fool" (Abrams ComicArts, 2019),

"Three Rocks" (Abrams ComicArts, 2023) and "Photographic Memory" ( Abrams ComicArts, 2025).

He is the recipient of the National Cartoonists Society's Reuben Award for Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year in 2022 and was

inducted into the Harvey Awards Hall of Fame in 2022.

Griffith presently lives and works in East Haddam, Connecticut.

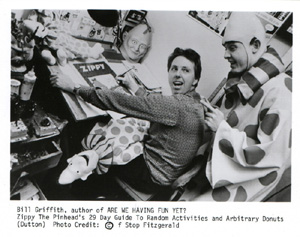

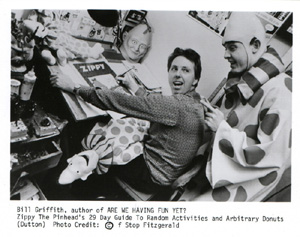

Photo below from 1985. Griffith shown with longtime Zippy stand-in Ron Brannan.

Below: Griffith's illustrious Great-Grandfather, William Henry Jackson,

at the Treasure Island World's Fair in San Francisco, 1939 (age 97).

Below: Bill Griffith in his studio, May 31, 2008.

ANOTHER BILL GRIFFITH BIO (from "Current Biography", 2001)

Zippy the Pinhead, a comic strip by the cartoonist Bill

Griffith, features a demented microcephalic in a polka-dotted muumuu who

spouts surreal aphorisms. The strip is, according to some, a

delightfully bizarre social commentary; it appears daily in more than

200 newspapers nationwide, including the San Francisco Chronicle, the

Washington Post, and the Boston Globe. Griffith's strips are collected

in the Zippy Quarterly, as well as a number of books, including Kingpin,

Zippy's House of Fun. His work has also been reprinted in German,

French, Swedish, Italian, Japanese, Dutch, Finnish, and Spanish, and it

has been featured in the New Yorker, National Lampoon, and various

comics magazines, such as Arcade, Yow, and Weirdo. Griffith, a member of

the San Francisco underground art scene, appeared in John O'Hagan's 1997

documentary Wonderland, a hilarious look at the suburban development in

Levittown, Long Island, where the cartoonist was raised. Zippy has been

the subject of at least two doctoral dissertations and has also been

cited as the inspiration for Saturday Night Live's popular recurring

characters the Coneheads. "A lot of people write angry letters saying

Zippy is stupid," Griffith told Mark Anderson for the Monthly (February

2000). "And that's why they don't get it: because it is stupid."

Initially referred to as Danny, Zippy is a microcephalic clown

based in part on the "pinheads" who appeared in Tod Browning's classic

1932 horror film, Freaks. In addition to the uncommon shape of their

heads, microcephalics are known for their childlike personalities and

rapid-fire speech. "Their scrambled attention spans struck me as a

metaphor for the way we get our doses of reality these days," Griffith

told Jon Randall and Wesley Joost for an interview in Goblin Magazine

that was reprinted on Zippy the Pinhead's official home page. "The kind

of fractured, short term information overload that we're all exposed to

every day." Griffith was also inspired by old posters of Zip the

What-Is-It?, an actual microcephalic who was featured in the Barnum &

Bailey sideshow from 1864 to 1926. (In 1975 Griffith became aware of a

remarkable coincidence--he and Zip the What-Is-It? shared the same name.

Griffith was named William Henry Jackson after his great-grandfather,

the old West photographer William H. Jackson; Zip the What-Is-It? was

born William Henry Jackson, in 1842.)

Griffith also had the good fortune to meet Dooley, an actual

"pinhead" whom a friend in Connecticut drove to work every day. The

cartoonist took notes as Dooley explained why Walter Cronkite was God

and uttered a dizzying stream of non sequiturs such as "Are you still an

alcoholic?" Similarly, Zippy responds to most situations with seemingly

out-of-context phrases including: "I just accepted provolone into my

life," "I just became one with my browser software," "Frivolity is a

stern taskmaster," and "All life is a blur of Republicans and meat."

Although several people, including the comedienne Carol Burnett, claimed

to have created it, the phrase "Are we having fun yet?" was in fact

first uttered by Zippy in the mid-70s and has been immortalized in

Bartlett's Familiar Quotations. "It is an expression of the American

existential dilemma, of anxiousness," Griffith explained to John

Marshall for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer (July 1, 1992). "The phrase

is supposed to be satirical, but lots of people don't see the subtext."

Griffith tolerated the line's appearance on countless bootleg T-shirts

and bumper stickers, but was particularly disturbed when it began to be

repeated by such mainstream cartoon characters as Garfield, Dennis the

Menace, and Ziggy.

Griffith described Zippy to Carolyn Baptista for the New York

Times (July 11, 1999) as a "walking subconscious." Zippy behaves like a

Zen master engaged in a gleeful exploration of pop culture. "Zippy is

living in the moment," Griffith explained to Baptista. "He's at peace

with himself because he's out of step with everyone; he doesn't know it,

and he doesn't care. . . . Zippy has no problem with the irrationality

of the universe, whereas most of us are desperately trying to make order

out of the universe, and our lives. Zippy accepts chaos as what it is,

which is the real order of everything." Zippy enjoys ding dongs and

taco sauce, and can often be found meditating about the washer at his

local laundromat. Most strips consist of a dialogue between Zippy and

Griffy, the cartoonist's neurotic alter ego, a judgmental type who

comments on the inescapable vapidity of consumer culture. In a

conversation with Gary Groth for the Comics Journal (March 1993),

Griffith described their relationship as the "manifestation of an inner

dialogue" between "the critic and the fool." "I think Zippy is part of

me, but I'm not Zippy. Whereas I'm more Griffy than I am not Griffy. . .

. Without that dialogue, the strip would probably sink into surrealism,

or, in Griffy's case, mere ranting and raving." Other characters include

the lovesick barroom philosopher Claude Funston; Zippy's wife, Zerbina;

and their children, Fuelrod and Meltdown.

Although he admires the work of many of his contemporaries,

including Ben Katchor, Matt Groening, and Mike Judge, Griffith has often

lamented the dumbing down of popular comic strips. He longs for the days

when newspapers printed graphically compelling and well-written stories,

such as Chester Gould's Dick Tracy and George Herriman's Krazy Kat. In

an article celebrating the 100th anniversary of the comic strip, which

appeared in the Boston Globe on November 10, 1996 and was reprinted on

Zippy's home page, Griffith explained that the shrinking space allotted

for comics has led to a dulling of certain artists' ambitions. "In this

Darwinian set-up, what thrives are simply drawn panels, minimal

dialogue, and a lot of head-and-shoulder shots. Anything more

complicated is deemed 'too hard to read.' A full, rich drawing style is

a drawback. Simplicity, even crudity, rules. . . . What we're left with

is a kind of childish, depleted shell of a once-vibrant medium. Comics

is a language. It's a language most people understand intuitively. If

cartoonists use a large and varied 'vocabulary' to entertain their

readers, those readers will usually come along for the ride."

Bill Griffith was born on January 20, 1944 in the New York City

borough of Brooklyn. He became interested in comics as a boy, reading

MAD magazine and following the adventures of Uncle Scrooge, Little Lulu,

and Plastic Man, but abandoned them for fine art in his teenage years.

His father was a career army man, whom Griffith described to Jon Randall

and Wesley Joost as a "completely frustrated, miserable human being";

his mother was a science-fiction writer who later wrote for True

Confessions. "She encouraged any artistic impulse I had, and my father

discouraged any artistic impulse I had," Griffith recalled to Randall

and Joost. "I had a very diametrically opposite set of parents," he told

Gary Groth. "Very understanding, hip, smart, creative mother, and a very

authoritarian, screwed-up, angry father." Encouraged along with many

other World War II veterans to retire, Griffith's father left the army;

he later reluctantly accepted a demotion to return to military service

as an ROTC instructor.

In 1955 Griffith's family moved to a ranch house in Levittown,

New York, where scores of identical homes had been quickly constructed

for World War II veterans by the developer William Levitt. "I always

thought of Levittown as a joke," he told Keith Bearden for Lowest Common

Denominator (Summer 1999), a print and on-line magazine from the

producers of the New Jersey radio station WFMU. "But it wasn't a joke to

my parents. Levittown was a dream come true. They never thought in a

million years they'd ever be able to own a house. But if you were a GI,

coming back from the war--no money down. Unfortunately what came out of

it was also kind of an imitation community with a lot of mindless

conformity." Griffith found the atmosphere of 1950s suburban America

stifling. "There was a deep sense of absurdity in Levittown, this kind

of self-conscious striving to be the ideal suburb, the ideal American

Leave-It-to-Beaver-Land," he was quoted as saying by Manuel Mendoza in

the Dallas Morning News (July 7, 1997, on-line). "It had kind of a stage

set quality to me, like we were all acting out some kind of TV sitcom

and everybody was reading lines and there was a laugh track in the

background."

Griffith took solace in his developing friendship with one

Levittown neighbor, the illustrator Ed Emshwiller, who designed covers

for many science-fiction and mystery books and magazines. "He didn't

point me to cartooning, but he pointed me into art in general and showed

me a way of understanding how within one artist, there could exist this

pop culture impulse and a fine art impulse," Griffith told Gary Groth.

Emshwiller recruited Griffith's parents as models on several occasions,

but Griffith was most proud when he himself appeared on the cover of the

September 1957 issue of Original Science Fiction. Emshwiller depicted

the 13-year-old Griffith riding a rocket ship to the moon as his father

yelled at him from a video screen. Griffith first encountered the

bohemian utopia that was Greenwich Village when he accompanied

Emshwiller into New York City for film screenings at Cinema 16, an

experimental film group that counted Emshwiller among its members. At 16

Griffith had a few poems published in local literary journals and

attended performances by Allen Ginsberg and Bob Dylan. (In 1978 Griffith

chronicled his years living next door to Emshwiller in a strip entitled

"Is There Life After Levittown?")

Hoping "to become Jackson Pollock Jr." as he put it to Carolyn

Baptista, Griffith studied fine art at the Pratt Institute of

Technology, in Brooklyn. He met cartoonist Kim Deitch, who introduced

him to such work as Little Nemo and Krazy Kat. Griffith was soon drawn

to the counterculture comics of R. Crumb and others, and he began to

draw again. "My first character was Mr. Toad," he told The World

Encyclopedia of Comics (1999), "a mean-spirited amphibian dressed in a

tight-fitting tweed suit." Mr. Toad appeared in such underground

magazines as Screw and the East Village Other. (It was not until 1992,

while working on a series about his father, that the cartoonist realized

that his father had been the inspiration for Mr. Toad.) Griffith told

Baptista that from the moment that he published his first comic strip,

"the wise guy inside me triumphed over the artiste. Of course it took me

years and years to realize that it was a demanding craft." In 1970

Griffith moved to San Francisco, which had become a haven for

underground artists. Shortly after arriving, he created Young Lust, a

parody of 1950s romance comics that featured the adventures of Randy and

Cherisse, shopping-mall dwellers who spent a lot of time in therapy; the

series was published in 1970.

Zippy the Pinhead made his debut in a strip entitled "I Gave My

Heart to a Pinhead and He Made a Fool Out of Me," in the first issue of

Real Pulp Comics, in 1970. Zippy began as a comic foil for Mr. Toad but

quickly superseded the egocentric amphibian. By 1976 Griffith's strips

ran weekly in the Berkeley Barb, and his work also appeared in High

Times. Arcade was a short-lived magazine that he co-edited with Art

Spiegelman, a cartoonist now well known for Maus, his two-volume

Pulitzer Prize-winning comic strip about the Holocaust. From 1973 to

1974, Griffith also worked with Spiegelman on Topps' Wacky Packages,

trading cards with parodies of everyday supermarket products. From 1976

to 1980 he syndicated Zippy through Rip Off Press, a publisher of

predominately underground comics; for the next six years, he syndicated

the strip himself. For three years, beginning in 1977, Griffith created

Griffith Observatory, a satiric look at the people and places he

encountered in his daily life.

In 1985 William Hearst III took over the San Francisco Examiner,

hiring both Griffith and the gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson. The

following year Zippy the Pinhead was picked up for syndication by King

Features. Griffith never imagined that he would have the opportunity to

create a daily strip; he later discovered that the person who had

brought the strip to King Features had been unhappy with his job and

intended to use its acquisition as a form of revenge. "He told me he

took Zippy because to him, Zippy was like leaving a ticking time bomb on

the doorstep of King Features," Griffith told Gary Groth. "Plus he was a

big Zippy fan. So he was indulging his taste, and thumbing his nose at

his boss as he left."

In October 1994 Griffith toured Cuba for two weeks, traveling on

a cultural-exchange visa, one of the only legal ways to circumvent the

United States' ban on commerce with that nation. He arrived during the

final days of a mass exodus, as thousands took advantage of Castro's

decision to permit emigration for a limited time and left the island on

rafts. Griffith's detailed observations of Cuban culture and politics

were published in a six-week series of strips during early 1995. In the

strips, in a style Griffith has called "cartoon-o-journalism," Zippy's

observations were combined with verbatim transcripts of conversations

Griffith had conducted with various Cubans, including artists,

government officials, and a Yoruba priestess.

In October 1998 Griffith and his wife, the cartoonist Diane

Noomin, left San Francisco, as chain stores such as Starbucks began to

proliferate and the character of the city changed. They moved to East

Haddam, Connecticut, a picturesque town on the banks of the Connecticut

River. Griffith's strips have always had a diarylike quality, and

Connecticut has provided the artist with plenty of material. "In a movie

theater a few days ago, I go to the candy counter, and there's this huge

menu--candy, popcorn, ice cream, pickles," he told Carolyn Baptista.

"They're selling individual pickles. How does this happen? Where am I?

So of course I came home and did a Zippy strip about it. It was too

surreal not too."

Griffith and Noomin have collaborated on nine drafts of a

screenplay for a live-action version of Zippy that has yet to be

produced. They have also attempted to develop an animated series. A

proposed series for the Showtime cable network came to naught because of

budget conflicts, and Griffith has turned down MTV twice because the

network insisted on owning the character.

Not everyone is amused by Zippy; editors frequently receive

angry letters from readers who find the strip incomprehensible.

"Suddenly, I'm talking to people in trailer camps in Memphis who say

Zippy promotes communism and masturbation," Griffith told James Kindall

for New York Newsday (December 11, 1988). Many are baffled by such

scenarios as the one in 1998 in which Zippy repeated the phrase

"Kaczynski Lewinsky Lipinski Lebowski" in four successive panels; its

publication inspired a number of e-mails from distressed readers. The

cartoonist told Mark K. Anderson that those who were confused by the

strip were most likely unfamiliar with jazz and therefore did not

"understand the musicality of language." Griffith believes that it is

the nature of satire to be limitless in scope, and that sometimes

readers just get lost. "I tend to just go all over the map; satire one

day, a surrealist gag the next and a political strip the day after

that," he explained to Kindall. "That's one of the reasons Zippy has

lasted so long. He can pretty much say or do what he wants. It's almost

like he has super powers, but all between his ears. He can't fly but he

can move pretty quickly on the ground." The strip can be ambiguous and

challenging and has often broached such heady subject matter as

existentialism and quantum physics. But Griffith has insisted that he

does not intend to be obscure. "I ask the audience to meet it halfway,"

he told Bob Andelman for Mr. Media (February 17, 1997, on-line). "As a

result, I'm self-limiting it to the audience it has. But the 200 papers

it's in are 185 more papers than I ever thought it would be in. So I'm

happy."

Griffith is acutely aware that his brand of satire is not in

great demand at present. "People are pretty complacent, but I think

we're headed for another big shakeup," he told Keith Bearden. "It's like

the '50s, where things were pretty bland, you also got Harvey Kurtzman

and Mad and the Beats. But the problem is that business and media [are]

incredibly savvy about co-opting rebellion at this point. They own it

before it ever has the chance to gel and mature into anything powerful

or threatening. It's to the point where you can convince a 30-year-old

that it's a form of individuality or rebellion to wear a logo or buy a

certain car."

Although Zippy's proclamations might seem incoherent at first,

Griffith maintains that most of what he says can be decoded with effort.

"He may be a pinhead," the cartoonist commented to James Kindall, "but

he's not without a point." Griffith sees Zippy's growing cult following

as a direct result of the American populace's shortened attention span.

"The greatest boon to Zippy has been the remote control devices on TV,"

he told Kindall. "Zippy's attention span is limited to a 15-second TV

commercial. I was doing Zippy way back when people were still having to

get up and change the channel. Their attention spans were shrinking but

it was still a stretch to get into Zippy's fast-paced, channel-changing

mentality. Now they're sitting there going click, click, click. I think

there's a price to pay when your brain cells get used to that all night

long. They're getting up to Zippy's speed."

--C.L.

Works by subject

Selected Books: Nation of Pinheads, 1982; Pointed Behavior,

1984; Zippy Stories, 1984; Pindemonium, 1986; Pinhead's Progress, 1989;

Get Me a Table Without Flies, Harry, 1990; From A to Zippy, 1991;

Griffith Observatory, 1993; Zippy's House of Fun, 1995; Zippy Annual,

2000

Works about subject

Suggested Reading: Comics Journal p50+ Mar. 1993, with photos;

Lowest Common Denominator p8+ Summer 1999; Monthly p5+ February 2000,

with photo; New York Times (Connecticut edition) p13 July 11, 1999, with

photo; Official Zippy the Pinhead home page; Seattle Post-Intelligencer

C p1+ July 1, 1992, with photo; Washington Post B p1 Apr. 8, 1995

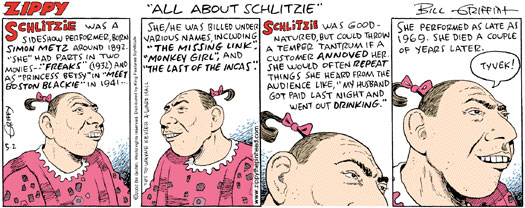

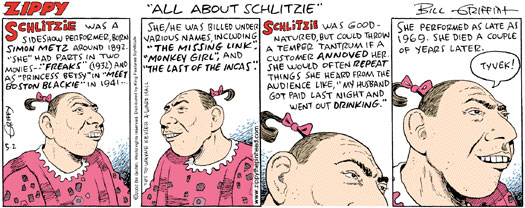

Above: "Schlitzie", a.k.a. "The Missing Link", "Monkey Girl" and "The Last Of The Incas",

born Simon Metz c. 1892. Died c. 1972. Had parts in two movies; "Freaks"

(1932, Tod Browning, dir.) and as "Princess Betsy" in "Meet Boston Blackie" (1941).

Shown here in a 1929 San Francisco press release.

BELOW: "Schlitzie" Zippy daily from 5/2/02. (NOTE: It was conformed recently

in an email from a reader who knew Schlitzie in his later years that Schlitzie was, indeed, a "he").

Below: Introduction to "Nancy Eats Food", 1989, Kitchen Sink Press

MORE BELOW

|