|

And why not, said Jerry A. McCoy, president of the Silver Spring Historical Society, who started the whole thing: Now the diner "will live forever in microfilm all across America." Said Tastee owner Gene Wilkes, who notes that business, after the move, is still on the rebound: "We enjoy any and all publicity that we can get."

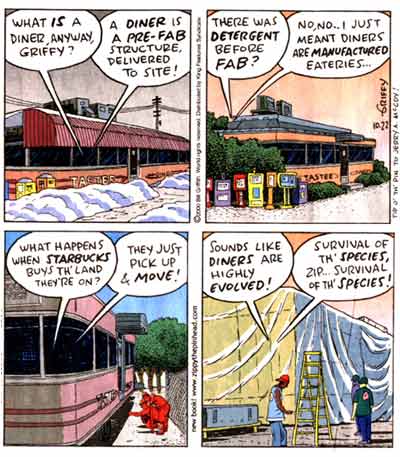

The Washington Post carries Zippy daily but not Sunday. So Sunday's Zippy is reprinted here.

First, a bit about the diner.

Last June, it made headlines when it was loaded aboard a giant trailer and carted from 8516 Georgia Ave. to a new location three blocks away at 8601 Cameron St. The diner had been on Georgia Avenue for five decades, slinging chipped beef and pork chops, chicken and dumplings and hometown, stainless-steel ambience.

It was threatened, though, when Discovery Inc., decided to move its headquarters from Bethesda to Silver Spring and use the land on which the diner stood. "We didn't own the land," Wilkes said.

But Tastee, one of the country's few remaining classic diners, had been named a Montgomery County Historic Landmark in 1994.

So on June 17, aided by funding from the county and state, the diner was hoisted onto a trailer and, while fans watched and police blocked traffic, was hauled a half-mile to the former parking lot that would be its new home.

Enter Jerry McCoy, champion of Silver Spring's history and loyal Zippy reader.

McCoy knew that Zippy's creator, Brooklyn-born Bill Griffith, a former West Coast underground cartoonist, had a thing for old-time eateries. "He has a great love of diners," McCoy said Monday. "He always incorporates diners into the story lines of his cartoons. You'll inevitably see Zippy sitting at a counter having a doughnut or a cup of coffee. He routinely draws actually named diners from all across America."

"When they moved the Tastee Diner back in June, I thought, 'Boy, this would be a great plot for one his strips,' " McCoy said. "I thought it was quite an unusual scene when it was rolling down Georgia Avenue."

McCoy e-mailed the details to Griffith. "It was incredible," McCoy said."Fifteen minutes later, I had a response from him. He said, 'Wow, this sounds like a great idea. Send me some more information, and I'll put it into the strip.' "

Strange and often baffling, Zippy is certainly not Peanuts, though the cartoon's observations and commentary often are profound and incisive.

Griffith, in an interview this week, said the strip was inspired partly by a 1932 film about sideshow characters. Among those in the film are people, like Zippy, with the rare neurological disorder, microcephaly, which often produces a small, pointed skull. Several appear in the film clad, like Zippy, in knee-length muumuus and wearing small tufts of top hair tied up in ribbons. The name Zippy, Griffith said, comes from that of a well-known 19th century microcephalic circus figure

dubbed "Zip the what-is-it."

Griffith said he has met several microcephalics. "They tend to be happy in a kind of out-of-control way," he said. "They're very verbal, with extremely short attention spans.

"It's almost like achieving a kind of enlightened state without effort," he said. "Granted, I wouldn't want to achieve it that way." In the strip, Zippy is just such a sage, with a day's worth of beard stubble and, in the color version, an orange and yellow polka-dot muumuu and white socks.

"Zippy's an infinitely flexible character to me," Griffith said from his home in East Haddam, Conn. "He can travel in time, or he can pop up in Bosnia one day and back in Connecticut the next day.

"I can use him as a vehicle to confront or deal with all kinds of social issues, whether I'm being critical or just being celebratory," he said.

Often, Griffith has Zippy and the strip's other characters speak from the venue of a diner, a weird out-of-the-way roadside attraction or another hunk of what he calls the country's "endangered reality."

"I grew up with diners," said Griffith, 56, who was reared on 1950s Long Island. "To me, the diner is a place where people are kind of open with each other. And Zippy is open all the time. He's open 24 hours a day.

"It's a place where you can sit down and start a fairly intimate or existential conversation with the guy sitting next to you at the counter," he said. "There's a sense of individuality and of uniqueness, kind of a sense of things slowed down . . . that the diner represents."

There's also a "relationship that's more direct between you and the server and the food, where you actually watch it being cooked," Griffith said, instead of the distant fast-food confrontation with "a smiling, robotic teenager."

Which is all very cosmic.

But Wilkes, the diner's owner, begs to add: "Every day, we have a minimum of three specials. It's not fast food. We have a chef in each kitchen. We do most everything from scratch."We cut our own steaks," he said. "Our hamburgers are not manufactured. They're not perfectly round. We actually press them with fresh beef that's never been frozen.

"We're not standard," he said, "by any means."

© 2000 The Washington Post

|

|